… a complex neurological condition which is constitutional in origin. The symptoms may affect many areas of learning and function, and may be described as a specific difficulty in reading, spelling and written language. One or more of these areas may be affected: Numeracy, notational skills (music), motor functions and organizational skills may also be involved. However, it is particularly related to mastering written language although oral language may be affected to some degree (The British Dyslexia Association, 1998; as cited in Helland, 2007, p. 26).

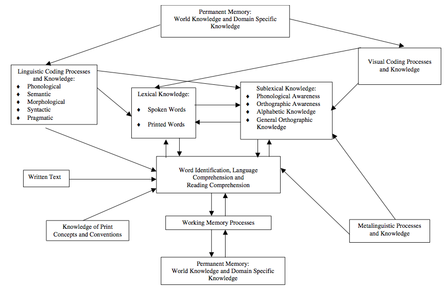

Before starting to talk about dyslexia in depth, it is necessary to mention the components of reading ability to have a better understanding of dyslexia. As I searched for this issue, I found that reading ability consists of “adequate language comprehension” and “fluent word identification”. In other words, “while written words are encoded symbolizations of spoken words, spoken words are encoded symbolizations of environmental experiences” (Vellutino et al., 2004, pg. 3). Thus, reading ability is a complex phenomenon that includes different types of knowledge and skills, which also depend on reading-related linguistic and non-linguistic cognitive abilities.

Therefore, since reading ability is composed of the complex interplay between these different memory systems and processes, Vellutino et al. (2004) state that difficulty in reading may come from the deficiencies in reading-related cognitive abilities resulting from abnormal development and malfunction in one or more of these coding and memory systems or from less mixture of reading-related cognitive abilities resulting from the interaction between the child’s experiences in her environment and “genetic endowment”. Hence, I will first discuss the manifest and underlying (cognitive and biological) causes of dyslexia and then I will move onto the discussion of what should be done to help dyslexic children.

To start with, research has shown that early reading difficulties basically manifest itself in deficiency in printed word identification besides deficiency in spelling and phonological decoding. According to this, Vellutino et al. (2004) define dyslexia as “a basic deficit in learning to decode print” (p. 6). Studies that examine the relationship between language comprehension and word identification have shown that even if the child is good at language comprehension, the child will still have the problem in reading comprehension (Gough & Tunmer, 1986; Perfetti, 1985; Snowling, 2000a; Stanovich, 1991; Vellutino, 1979, 1987; Vellutino, Scanlon, & Tanzman, 1994; Vellutino, Scanlon, & Chen, 1995a; Vellutino et al., 1996, as cited in Vellutino et al., 2004). On the contrary, these studies also report that if the child has deficiency in reading comprehension, she will also have deficiency in word identification and word level skills such as spelling and phonological decoding. Therefore, it is possible to say that word identification, which results from difficulty in learning to decode print, is the most basic cause of dyslexia.

Apart from these studies, there are naturalistic studies, intervention studies, and controlled laboratory studies which have found out that deficiency in phonological awareness and alphabetic code may lead to difficulty in reading (Vellutino et al., 2004). In addition to this, as shown in the model above, phonological awareness and alphabetic code are two components of metalinguistic analysis (analysis of language structures), and orthographic awareness and general orthographic knowledge are the other two components. As a result, Vellutino et al. (2004) state that children who have difficulty in phonological awareness and alphabetic code will also have difficulty in orthographic awareness and general orthographic knowledge since there is a reciprocal relationship among them. Thus, in addition to the difficulty in identifying printed words, difficulties in phonological awareness and alphabetic code also result in difficulties in reading.

Yet, Vellutino et al. (2004) question whether these deficiencies are causally related to dyslexia. They further state that although aforementioned studies have found out evidence that limitations in knowledge of print concepts have been observed to lead to early language difficulties, they are not the basic causes of dyslexia in the biological sense since these deficiencies are mostly led by “experiential and instructional deficits” instead of “biologically based cognitive deficits” (p. 7). This result is supported by studies which indicate that children who are good at metalinguistic analysis and identifying printed words have still difficulty in learning to read (Vellutino et al., 1996, as cited in Vellutino et al. 2004).

As a consequence, it is important to discuss the underlying (cognitive and biological) causes of dyslexia:

For many years, cognitive deficits have been studied as the basic causes of dyslexia (Fletcher, Foorman, Shaywitz, & Shaywitz, 1999; Lyon et al., 2002; Snowling, 2000a; Vellutino, 1979, 1987; Vellutino & Scanlon, 1982, as cited in Vellutino et al., 2004). For instance, dyslexia has been ascribed to the difficulties in selective attention (Douglas, 1972, as cited in Vellutino et al., 2004) and associative learning (Brewer, 1967; Gascon & Goodglass, 1970; as cited in Vellutino et al. 2004). Thus, difficulties in one or more of these general learning abilities have been thought to lead to specific language disability (dyslexia). Yet, empirical research has disproved the theories under general learning abilities as the basic causes of dyslexia since these theories did not eliminate group differences in verbal coding ability and working memory processes that could be influenced by verbal coding deficits (Vellutino, 1979, 1987; Vellutino & Scanlon, 1982; see also Katz, Shankweiler, & Liberman, 1981; Katz, Healy, & Shankweiler, 1983; as cited in Vellutino et al., 2004). Visual deficit theories were popular in the 1970s and 1980s, and when linguistic deficit theories started to compete with visual deficit theories, visual deficit theories lost their popularity due to lack of empirical support. Other than these, some language related theories emerged as many scholars thought that since language is a linguistic skill, deficiencies in semantic, phonological, or syntactic knowledge would lead to dyslexia.

Apart from these factors, neurobiological factors have been considered as the underlying causes of dyslexia and studies on brain structure, brain function, and genetics have been conducted. Regarding brain structure, post mortem studies and anatomical magnetic resonance imaging have been carried out. Post mortem studies focus on the structure of temporal lobe known as the “planum temporale”. In normal adults, this structure has been reported as larger in the left hemisphere. Yet, according to post portem studies, there are unexpected symmetries in the left versus right hemispheres of dyslexics, that is, symmetry is seen as the cause of dyslexia (Galaburda, Sherman, Rosen, Aboitiz, & Geschwind, 1985; Humphreys, Kaufmann, & Galaburda, 1990; as cited in Vellutino et al. 2004). Yet, since it is difficult to find available brains for such studies and to control learners’ backgrounds and characteristics on the basis of post mortem studies, neuroimaging has emerged. Anatomical magnetic resonance imaging (aMRI) has been used to conduct studies about the causes of dyslexia. Although a wide range of structures have been evaluated including planum temporale, temporal lobes, and corpus callosum, aMRI is time-consuming and requires human effort that in turn puts constraints on the size of the samples. In addition, since there is variety in the measurement of brain structures, it is possible to have mixed results. As for brain function, functional neuroimaging methods are used in order to collect information about the response of the brain to cognitive challenges. There are five methods that are used: PET, fMRI, MSI, MRS, and electrophysiological methods.

Shaywitz et al. (2005) report that functional brain imaging studies are important because they have been also used to “describe the organization of brain for reading, specifically identification and localization of specific neural systems serving reading and their differences in typical and dyslexic readers” (p. 279). According to the results of these studies, there are three left hemisphere neural systems for reading and good readers show much more activation in the three left hemisphere neural systems than do dyslexic children. With maturation, there is compensation “in anterior regions around the inferior frontal gyrus, so that differences between older nonimpaired and dyslexic children are confined to two posterior regions, the parieto-temporal and occipito-temporal systems” (Shaywitz et al., 2002, as cited in Shaywitz et al., 2005, p. 279). Another conclusion from these studies is that “poor home and educational environment could be jointly responsible for the concurrent expression of low IQ and poor reading” (Olson, 1999, as cited in Shaywitz et al. 2005, p. 280).

At this point, it is possible to say that dyslexia has a neurobiological basis, but one should not also disregard the possible effects of school and home environments and cultures in which children learn how to read on dyslexia because reading is a complex phenomenon. Yet, now it’s time to talk about what all this means for the future. First, the research on the causes of dyslexia is important for people who work in school systems because the research reviewed here questions the use of the psychometric assessment as the only means for determining the main causes of reading difficulties for purposes of educational planning, that is, the research is against the assessment to determine underlying (cognitive and biological) and manifest causes of dyslexia because such research results in the classification such as learning disabled children versus socioeconomically disadvantaged children. As a result of this, the child’s reading difficulty is attributed to a cognitive deficit and then to neuro-developmental anomaly. However, as also pointed out earlier, psychometric approaches do not have a control on the child’s educational background and early experiences and most early reading difficulties are caused primarily by experiential and instructional deficits. Therefore, although I have categorized the causes of dyslexia as manifest and underlying, it should be clear that there are no clear-cut criteria to determine the ultimate origin of a child’s early reading difficulty as neuro-biological. Hence, the question that should be answered is what can be done to help dyslexic children.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework for designing curriculum that can help teachers to differentiate instruction for differing learners. UDL can allow educators to design curricula from the beginning to address individual differences; therefore, disabled curricula can be reduced and be flexible and customized via new interactive, flexible, and malleable media. Thus, by applying the UDL principles to the creation of web-based materials, educators can provide their students with an environment that supports all learners and one such technology that they can use as a guide for technology integration in their classroom is Text-to-Speech Technology (TTST) which will not only support their students but also will address to the special needs of their dyslexic students. TTST aims to support students who struggle to read or have a reading disorder. Today nearly all computers come with some basic TTST programs. Most TTST programs can speak letters, words, and/or sentences as they are typed, but of course TTST programs are most helpful if they highlight the words as they are spoken because I think they could help dyslexic students focus their attention on the text, understand the text, and most importantly be aware of their learning needs as dyslexic students’ strength is not in the visual modality. They could also help students to express themselves better because dyslexic children face barriers when they try to access information via print materials. TTST could also mean a shift in focus in school systems, that is, rather than focusing on the psychometric assessment to determine the causes of dyslexia, the integration of TTST into the classroom could mean a step to provide differentiated support in the classroom and to develop effective educational programs for helping dyslexic children.

To conclude, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Albert Einstein, Thomas Edison, and Walt Disney are all dyslexics; yet they are known as the best representatives of their fields. That is, being dyslexic cannot stop someone from achieving her goals. Let’s not kill creativity in our students!

Some Free TTST Resources

Accessibar : It is a Firefox browser extension that adds visual accommodation tools and text-to-speech. http://accessibar.mozdev.org/

ATBar: As well as text to speech, it offers other tools such as changing the layout of the web page to make it easier to read and using spell checking and word prediction when writing on pages, but no high-lighting. https://www.atbar.org/

Balabolka: It can speak with synchronized highlighting. It colors the text, and leaves the color on what has been read. It can create mp3 files.

http://www.cross-plus-a.com/balabolka.htm

CLiCk, Speak : A Firefox browser extension that adds text-to-speech. Students can hear web pages read aloud. http://clickspeak.clcworld.net/

Natural Reader: Write in, or copy and paste into, its own word processor for synchronized highlighting. http://www.naturalreaders.com/

ReadingBar: It adds text- to-speech to Internet Explorer on Window. Web. It can save web pages to audio and can enlarge the graphics and text on a web page. http://www.readplease.com/

REFERENCES

Helland, T. (2007). Dyslexia at a behavioral and a coginitive Level. DYSLEXIA, 13, 25-41. Retrieved from DOI: 10.1002/dys.325

Shaywitz, S. E., Mody, M., Shaywitz B. A. (2005). Neural mechanisms in dyslexia. Association for Psychological Science, 15 (6), 278-281. Retrieved from http://dyslexia.yale.edu/current_directions_in_psych_science_2006.pdf

Vellutino, F. R., Fletcher J. M., Snowling M. J., Scanlon, D. M. (2004). Specific

reading disability: what we have learnt in the past four decades? Journal of Child Psychiology and Psychiatry, 45 (1), 2-40. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1046/j.00219630.2003.00305.x/asset/j.00219630.2003.00305.x.pdf?v=1&t=hhgx5p5h&s=13bb943b8ec38ba2fa7b36c21a63bebc4d574f2c

Woliver, R. (2008). Alphabet kids - from ADD to Zellweger syndrome: a guide to

developmental, neurobiological and psychological disorders for parents and professionals. London: Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed