Passion and curiosity are massive driving forces that give me a deep purpose to learn and to teach. Technology allows me to not only learn in a new and different way, but also to teach my students in a much more creative way. Thus, as an educator, my mission is to educate my students not only by teaching but also making use of available technologies to help them build their understanding of the technology as a part of the education process and to increase their motivation. My vision is to help my students to graduate with 21st century skills to succeed in work and life and to be productive members of the society so that my students will be good explorers and communicators of knowledge by using technology while I also expand my role of teaching from teacher to a facilitator, modeler, learning architect, connected learner, change agent, and synthesizer.

Therefore, I use technology in many ways because I believe it better demonstrates my passion and curiosity. I use technology to find answers to my questions and to accomplish my goals. I connect with other teachers through social networking, blogging, and online courses. When I have a question in mind, I send it out to these people whose personal interests or expertise can help me to find answers to my questions or to solve my problems. I use mails, group discussion boards, wikis, blogs, Google docs, Twitter, and Facebook to connect with these people. I use social bookmarking tools to manage and organize bookmarks of resources online because just like other people, I have those days that I struggle to keep track of new ideas. I also use technology to create new tools to address the needs of my students better.

As for how I use technologies to inspire passion and curiosity in my classroom, technology in my classroom is used for communicating and working collaboratively, facilitating student learning and creativity, using critical thinking skills to plan research and to manage projects, modeling instruction, record keeping, and sharing work. To accomplish that, I teach using videos, podcasts, online graphic organizers, interactive online activities, webquests, and websites. I also make use of the interactive white board I have in my classroom. I also use numerous tech tools to teach and among my favorites are Glogster, Prezi, Powtoon, Voicethread, Weebly, Mind Meister, and Facebook.

In conclusion, I believe the process of learning is devalued by focusing on the result. We, as teachers, need to honor that process and our students’ desire for passion and curiosity. Technology is a great way to inspire passion and curiosity in our classroom because if the content is presented in different ways and provides options for learners, then it can be guaranteed that information is accessible to learners with different learning styles and comprehension is also easier for many students in the class.

Please find below my something I created using something. It highlights the main ideas from this post.

Purpose

The purpose of the survey was to collect data on the ways my colleagues currently use technologies, would like to use technologies, and would like to engage in professional development about technology integration at work. This information would be used to guide the planning and implementation of future professional development trainings. This report presents the results collected through the Professional Development Needs Assessment in Technology survey.

Methods

I created a survey using Google Forms and sent it to my colleagues. 34 responses were collected. Data collection began June 10, 2013 and ended June 15, 2013.

Organization of Report

This report is divided into three sections:

· Teacher demographics: data on my colleagues’ years of experience

· Open-ended responses: data on my colleagues’ responses to two open-ended questions regarding the ways my colleagues currently use technologies and would like to use technologies

· Teachers’ professional development and technology: data on my colleagues’ interests in particular forms of professional development

Teacher Demographics

Years of Experience

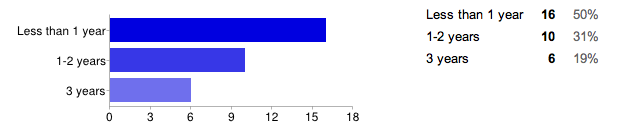

Most participants in this survey (50%) have less than 1 year of experience. Those with 1-2 years of experience are the second largest group (31%).

Open-ended Responses

My colleagues responded two open-ended questions in the survey. These questions were:

1. How do you utilize technology in your daily lessons?

2. In what ways would you like to change or improve how you use technology in your classroom?

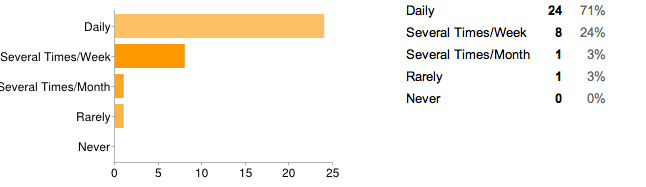

Before summarizing the responses to these questions, it is important to note that most of my colleagues (71%) use technology daily during instruction. Yet, the result is not surprising as all teachers in our university are given laptops to take home so they can integrate technology into their classrooms and carry on preparing resources and other materials ready for school.

1. How do you utilize technology in your daily lessons?

After reviewing responses from my colleagues, I noticed some trends. Most of my colleagues use Microsoft PowerPoint or Word. They also use videos/YouTube in their teaching in addition to the coursework software, CDs, and DVDs that accompany the books. Facebook is highly familiar to my colleagues and also the most popular social network integrated into the classroom while some other social media tools such as blogs, wikis, and Google sites are less used to teach. Most of my colleagues also use technology to project websites, worksheets, and presentations on the board.

2. In what ways would you like to change or improve how you use technology in your classroom?

We have interactive whiteboards in our classrooms, but the majority of my colleagues felt that they needed training on how to thoroughly exploit the smart board. My colleagues are especially interested in learning more about Web 2.0 tools and smart phone applications. Although the biggest concern by my colleagues is that they use technology in the traditional sense such as using the projectors, PPTs, and some websites, they are all eager to learn more about technology because they believe that integrating technology into their classrooms can increase student engagement.

Teachers’ Professional Development and Technology

1. Technology-focused Professional Development

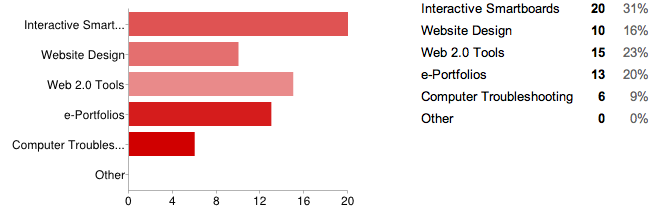

The majority of responses from my colleagues (31%) are requests for trainings with interactive whiteboards. The second largest group of responses (23%) is requests for trainings on the use of Web 2.0 Tools and the third largest group (20%) indicates a desire for training on e-Portfolios. Finally, the fourth group of responses (16%) points toward an interest in training on Website Design and the fifth group of responses is requests for training in Computer Troubleshooting.

2. Professional Development Delivery Format Preferences

More than half of my colleagues (59%) indicate a preference for a combination of both while 29% indicate a preference for face-to-face professional development. Finally, 12% indicate a preference for online/distance learning.

Conclusions

Overall, the findings from this survey offer three conclusions. First of all, most of my colleagues integrate technology into their classrooms on a daily basis, yet they feel that they are using basic technology tools. Thus, future trainings should address this issue and focus on how teachers can use the technology in their teaching. Secondly, my colleagues seem interested in both online professional development and face-to-face professional development; therefore, online forms of professional development should also be implemented in our program. Finally, I believe that we need a carefully designed technology plan to effectively use technology in our teaching as clear goals for the use or integration of technology can increase confidence and willingness of my colleagues to use technology to create a rich and meaningful instruction for our students. Therefore, I will be working on planning technology related professional development starting this summer as I know that my colleagues value technology as an important part of our program. I hope that consistent professional development opportunities will help to make effective use of existing and emerging digital tools in support of student learning.

To all my colleagues,

Thank you for your time in providing this important information. The purpose of the survey is to collect data on the ways you currently use technologies, would like to use technologies, and would like to engage in professional development about technology integration at work.

Thank you:)

In the 21st century, the intensification of globalization has made global transaction easier and led to the growth of international finance indifferent to the constraints of time and space, resulting in the commodification of knowledge, that is, the advent of the mass media has created information societies in which knowledge is something that can be traded in the market-place. In addition to the marketization of information, the globalization of economy has also shifted the focus from education and schooling to learning. As a result of this, the definition of learning has changed and Shahrzad Mojab (2009) defines this new kind of learning as ‘learning by dispossession’, by which I mean that in the process of learning and work something other than ‘learning’ (which can be measured, evaluated or assessed on the basis of categorisation of ‘formal’, ‘informal’ and ‘non-formal’, or ‘paid’ and ‘unpaid’) is happening. (p. 14) In other words, this learning places the responsibility for lifelong learning not on the state but on the individual and has a neutral meaning. Therefore, it is the learner who defines learning based on their preferences and takes action for their own learning. Yet, to choose responsibly from the massive amounts of information available in our networked world, learners should participate as reflective consumers in a market. To this end, I decided to revisit my own infodiet. My current infodiet consists of facebook, twitter, and various websites and I am well aware that although my infodiet should open up many doors to sources of information, it still needs to be controlled and organized due to the growing number of new technologies. Thus, I decided to add some new resources to my infodiet because I realized that they would make my definition of “learning” more meaningful, more delicious, and most importantly more like me. To start with, for my continuous professional development, I chose to follow @iateflonline and @AAEEBL. IATEFL is one of the biggest communities of ELT teachers in the world and each spring they organize The IATEFL International Annual Conference and Exhibition; therefore, to watch recorded video talks and interviews, to share ideas with other teachers in the world, and to stay up to date with new developments in the ELT world I am now following IATEFL. Additionally, nowadays I am interested in learning more about eportfolios because I believe in the value of eportfolio for learning. That’s why, I decided to follow AAEEBL because it provides me with an opportunity to watch conferences and webinars and helps me to find online eportfolio resources and to follow news about the upcoming eportfolio events. My second group of new resources is focused on news on teaching because teaching is what I do in the classroom. They include @GuardianTeach and @tedtalks. I think following these is a great way to keep connected to my work life because by reading the articles on GuardianTeach and by watching the videos on TedTalks I can find solutions to the problems that I face in the classroom and also I can find the opportunity to reflect on my own teaching. Finally, for news and updates on technology, I chose to follow @TechCrunch and @TechSmith. Technology is an indispensable part of my life and an indispensable aid to my colleagues and students; thus, it is crucial that I am up to date on what is happening in the world of technology. To conclude, I feel happy to have added to my infodiet because I believe it is my responsibility to choose what to learn as a self-directed, responsible, lifelong learner! REFERENCES Mojab, S. (2009). Turning work and lifelong learning inside out: A marxist-feminist attempt. In L. C. & S. W. (Eds.), Turning work and lifelong learning inside out (pp. 4-15). South Africa: HSRC Press. The Ontario Institute for Catholic Education (2011). I am a learner for life [Image]. Retrieved from http://www.iceont.ca/page1787306.aspx

“Hav ingdys lexiac anmake it hardtoread! Translation: Having dyslexia can make it hard to read” (Woliver, 2008). So what is dyslexia? The British Dyslexia Association defines dyslexia as

… a complex neurological condition which is constitutional in origin. The symptoms may affect many areas of learning and function, and may be described as a specific difficulty in reading, spelling and written language. One or more of these areas may be affected: Numeracy, notational skills (music), motor functions and organizational skills may also be involved. However, it is particularly related to mastering written language although oral language may be affected to some degree (The British Dyslexia Association, 1998; as cited in Helland, 2007, p. 26).

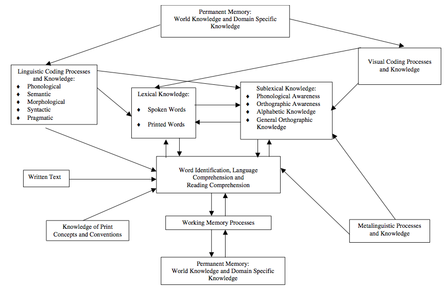

Before starting to talk about dyslexia in depth, it is necessary to mention the components of reading ability to have a better understanding of dyslexia. As I searched for this issue, I found that reading ability consists of “adequate language comprehension” and “fluent word identification”. In other words, “while written words are encoded symbolizations of spoken words, spoken words are encoded symbolizations of environmental experiences” (Vellutino et al., 2004, pg. 3). Thus, reading ability is a complex phenomenon that includes different types of knowledge and skills, which also depend on reading-related linguistic and non-linguistic cognitive abilities.

Figure 1. Cognitive processes and different types of knowledge entailed in learning to read. The model indicates the cognitive processes and other types of knowledge involved in reading ability (Vellutino et al., 2004, p. 4). Therefore, since reading ability is composed of the complex interplay between these different memory systems and processes, Vellutino et al. (2004) state that difficulty in reading may come from the deficiencies in reading-related cognitive abilities resulting from abnormal development and malfunction in one or more of these coding and memory systems or from less mixture of reading-related cognitive abilities resulting from the interaction between the child’s experiences in her environment and “genetic endowment”. Hence, I will first discuss the manifest and underlying (cognitive and biological) causes of dyslexia and then I will move onto the discussion of what should be done to help dyslexic children. To start with, research has shown that early reading difficulties basically manifest itself in deficiency in printed word identification besides deficiency in spelling and phonological decoding. According to this, Vellutino et al. (2004) define dyslexia as “a basic deficit in learning to decode print” (p. 6). Studies that examine the relationship between language comprehension and word identification have shown that even if the child is good at language comprehension, the child will still have the problem in reading comprehension (Gough & Tunmer, 1986; Perfetti, 1985; Snowling, 2000a; Stanovich, 1991; Vellutino, 1979, 1987; Vellutino, Scanlon, & Tanzman, 1994; Vellutino, Scanlon, & Chen, 1995a; Vellutino et al., 1996, as cited in Vellutino et al., 2004). On the contrary, these studies also report that if the child has deficiency in reading comprehension, she will also have deficiency in word identification and word level skills such as spelling and phonological decoding. Therefore, it is possible to say that word identification, which results from difficulty in learning to decode print, is the most basic cause of dyslexia. Apart from these studies, there are naturalistic studies, intervention studies, and controlled laboratory studies which have found out that deficiency in phonological awareness and alphabetic code may lead to difficulty in reading (Vellutino et al., 2004). In addition to this, as shown in the model above, phonological awareness and alphabetic code are two components of metalinguistic analysis (analysis of language structures), and orthographic awareness and general orthographic knowledge are the other two components. As a result, Vellutino et al. (2004) state that children who have difficulty in phonological awareness and alphabetic code will also have difficulty in orthographic awareness and general orthographic knowledge since there is a reciprocal relationship among them. Thus, in addition to the difficulty in identifying printed words, difficulties in phonological awareness and alphabetic code also result in difficulties in reading. Yet, Vellutino et al. (2004) question whether these deficiencies are causally related to dyslexia. They further state that although aforementioned studies have found out evidence that limitations in knowledge of print concepts have been observed to lead to early language difficulties, they are not the basic causes of dyslexia in the biological sense since these deficiencies are mostly led by “experiential and instructional deficits” instead of “biologically based cognitive deficits” (p. 7). This result is supported by studies which indicate that children who are good at metalinguistic analysis and identifying printed words have still difficulty in learning to read (Vellutino et al., 1996, as cited in Vellutino et al. 2004). As a consequence, it is important to discuss the underlying (cognitive and biological) causes of dyslexia: For many years, cognitive deficits have been studied as the basic causes of dyslexia (Fletcher, Foorman, Shaywitz, & Shaywitz, 1999; Lyon et al., 2002; Snowling, 2000a; Vellutino, 1979, 1987; Vellutino & Scanlon, 1982, as cited in Vellutino et al., 2004). For instance, dyslexia has been ascribed to the difficulties in selective attention (Douglas, 1972, as cited in Vellutino et al., 2004) and associative learning (Brewer, 1967; Gascon & Goodglass, 1970; as cited in Vellutino et al. 2004). Thus, difficulties in one or more of these general learning abilities have been thought to lead to specific language disability (dyslexia). Yet, empirical research has disproved the theories under general learning abilities as the basic causes of dyslexia since these theories did not eliminate group differences in verbal coding ability and working memory processes that could be influenced by verbal coding deficits (Vellutino, 1979, 1987; Vellutino & Scanlon, 1982; see also Katz, Shankweiler, & Liberman, 1981; Katz, Healy, & Shankweiler, 1983; as cited in Vellutino et al., 2004). Visual deficit theories were popular in the 1970s and 1980s, and when linguistic deficit theories started to compete with visual deficit theories, visual deficit theories lost their popularity due to lack of empirical support. Other than these, some language related theories emerged as many scholars thought that since language is a linguistic skill, deficiencies in semantic, phonological, or syntactic knowledge would lead to dyslexia. Apart from these factors, neurobiological factors have been considered as the underlying causes of dyslexia and studies on brain structure, brain function, and genetics have been conducted. Regarding brain structure, post mortem studies and anatomical magnetic resonance imaging have been carried out. Post mortem studies focus on the structure of temporal lobe known as the “planum temporale”. In normal adults, this structure has been reported as larger in the left hemisphere. Yet, according to post portem studies, there are unexpected symmetries in the left versus right hemispheres of dyslexics, that is, symmetry is seen as the cause of dyslexia (Galaburda, Sherman, Rosen, Aboitiz, & Geschwind, 1985; Humphreys, Kaufmann, & Galaburda, 1990; as cited in Vellutino et al. 2004). Yet, since it is difficult to find available brains for such studies and to control learners’ backgrounds and characteristics on the basis of post mortem studies, neuroimaging has emerged. Anatomical magnetic resonance imaging (aMRI) has been used to conduct studies about the causes of dyslexia. Although a wide range of structures have been evaluated including planum temporale, temporal lobes, and corpus callosum, aMRI is time-consuming and requires human effort that in turn puts constraints on the size of the samples. In addition, since there is variety in the measurement of brain structures, it is possible to have mixed results. As for brain function, functional neuroimaging methods are used in order to collect information about the response of the brain to cognitive challenges. There are five methods that are used: PET, fMRI, MSI, MRS, and electrophysiological methods. Shaywitz et al. (2005) report that functional brain imaging studies are important because they have been also used to “describe the organization of brain for reading, specifically identification and localization of specific neural systems serving reading and their differences in typical and dyslexic readers” (p. 279). According to the results of these studies, there are three left hemisphere neural systems for reading and good readers show much more activation in the three left hemisphere neural systems than do dyslexic children. With maturation, there is compensation “in anterior regions around the inferior frontal gyrus, so that differences between older nonimpaired and dyslexic children are confined to two posterior regions, the parieto-temporal and occipito-temporal systems” (Shaywitz et al., 2002, as cited in Shaywitz et al., 2005, p. 279). Another conclusion from these studies is that “poor home and educational environment could be jointly responsible for the concurrent expression of low IQ and poor reading” (Olson, 1999, as cited in Shaywitz et al. 2005, p. 280). At this point, it is possible to say that dyslexia has a neurobiological basis, but one should not also disregard the possible effects of school and home environments and cultures in which children learn how to read on dyslexia because reading is a complex phenomenon. Yet, now it’s time to talk about what all this means for the future. First, the research on the causes of dyslexia is important for people who work in school systems because the research reviewed here questions the use of the psychometric assessment as the only means for determining the main causes of reading difficulties for purposes of educational planning, that is, the research is against the assessment to determine underlying (cognitive and biological) and manifest causes of dyslexia because such research results in the classification such as learning disabled children versus socioeconomically disadvantaged children. As a result of this, the child’s reading difficulty is attributed to a cognitive deficit and then to neuro-developmental anomaly. However, as also pointed out earlier, psychometric approaches do not have a control on the child’s educational background and early experiences and most early reading difficulties are caused primarily by experiential and instructional deficits. Therefore, although I have categorized the causes of dyslexia as manifest and underlying, it should be clear that there are no clear-cut criteria to determine the ultimate origin of a child’s early reading difficulty as neuro-biological. Hence, the question that should be answered is what can be done to help dyslexic children. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework for designing curriculum that can help teachers to differentiate instruction for differing learners. UDL can allow educators to design curricula from the beginning to address individual differences; therefore, disabled curricula can be reduced and be flexible and customized via new interactive, flexible, and malleable media. Thus, by applying the UDL principles to the creation of web-based materials, educators can provide their students with an environment that supports all learners and one such technology that they can use as a guide for technology integration in their classroom is Text-to-Speech Technology (TTST) which will not only support their students but also will address to the special needs of their dyslexic students. TTST aims to support students who struggle to read or have a reading disorder. Today nearly all computers come with some basic TTST programs. Most TTST programs can speak letters, words, and/or sentences as they are typed, but of course TTST programs are most helpful if they highlight the words as they are spoken because I think they could help dyslexic students focus their attention on the text, understand the text, and most importantly be aware of their learning needs as dyslexic students’ strength is not in the visual modality. They could also help students to express themselves better because dyslexic children face barriers when they try to access information via print materials. TTST could also mean a shift in focus in school systems, that is, rather than focusing on the psychometric assessment to determine the causes of dyslexia, the integration of TTST into the classroom could mean a step to provide differentiated support in the classroom and to develop effective educational programs for helping dyslexic children. To conclude, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, Albert Einstein, Thomas Edison, and Walt Disney are all dyslexics; yet they are known as the best representatives of their fields. That is, being dyslexic cannot stop someone from achieving her goals. Let’s not kill creativity in our students! Some Free TTST Resources Accessibar : It is a Firefox browser extension that adds visual accommodation tools and text-to-speech. http://accessibar.mozdev.org/ ATBar: As well as text to speech, it offers other tools such as changing the layout of the web page to make it easier to read and using spell checking and word prediction when writing on pages, but no high-lighting. https://www.atbar.org/ Balabolka: It can speak with synchronized highlighting. It colors the text, and leaves the color on what has been read. It can create mp3 files. http://www.cross-plus-a.com/balabolka.htm CLiCk, Speak : A Firefox browser extension that adds text-to-speech. Students can hear web pages read aloud. http://clickspeak.clcworld.net/ Natural Reader: Write in, or copy and paste into, its own word processor for synchronized highlighting. http://www.naturalreaders.com/ ReadingBar: It adds text- to-speech to Internet Explorer on Window. Web. It can save web pages to audio and can enlarge the graphics and text on a web page. http://www.readplease.com/ REFERENCES Helland, T. (2007). Dyslexia at a behavioral and a coginitive Level. DYSLEXIA, 13, 25-41. Retrieved from DOI: 10.1002/dys.325 Shaywitz, S. E., Mody, M., Shaywitz B. A. (2005). Neural mechanisms in dyslexia. Association for Psychological Science, 15 (6), 278-281. Retrieved from http://dyslexia.yale.edu/current_directions_in_psych_science_2006.pdf Vellutino, F. R., Fletcher J. M., Snowling M. J., Scanlon, D. M. (2004). Specific reading disability: what we have learnt in the past four decades? Journal of Child Psychiology and Psychiatry, 45 (1), 2-40. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1046/j.00219630.2003.00305.x/asset/j.00219630.2003.00305.x.pdf?v=1&t=hhgx5p5h&s=13bb943b8ec38ba2fa7b36c21a63bebc4d574f2c Woliver, R. (2008). Alphabet kids - from ADD to Zellweger syndrome: a guide to developmental, neurobiological and psychological disorders for parents and professionals. London: Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed